A key task of psychotherapy is to help someone understand their own cognitive and emotional processes better. It is often the case that our own ways of thinking, feeling and behaving are so habitual that we take them for granted. Because we can’t see them clearly, or see them at all, we don’t question them.

A key task of psychotherapy is to help someone understand their own cognitive and emotional processes better. It is often the case that our own ways of thinking, feeling and behaving are so habitual that we take them for granted. Because we can’t see them clearly, or see them at all, we don’t question them.

One to one, a psychotherapist has various ways of bringing those hidden or unrecognised processes into conscious awareness. Since we have no choice over something we can’t see, self-awareness is especially important when established ways of thinking or habitual emotional responses create an unhealthy and self-defeating cycle. Once our habitual responses are recognised, we have knowledge, insight, and therefore new choices.

This article is about one method of getting to know yourself better that can be done alone, outside the therapy room; a method that can also enhance what happens in psychotherapy sessions: the left/right journal.

The origin of the idea

Many years ago I was in the audience at an event at which the speaker on stage said, “I’m an academic, so I only write on the left hand page. The right hand page is for adding notes.” Her assumption appeared to be that this is what all academics do. That may have been true where she worked, but to me it was a novel idea and I haven’t come across it again since. It struck me as a way of writing that one day could have a therapeutic application.

It was some time later that this gestated into the left/right journal as a way of helping clients gain insight and self-awareness. I have suggested it to many clients since with positive results, helping to bring self-understanding and therefore personal change.

The first step is to buy a book to use as the journal and, if you live with others, to have a private place to keep it.

The left page: capturing a moment in time

On the left page only, write your concerns. This is best done regularly, at the same time once or twice a week. It is also important to write additional entries when emotions – sadness, anger, fear – are high, and the familiar cycle of problems appears again, or when you feel particularly stuck.

The following pointers will help make writing on the left page productive.

Don’t worry too much about spelling, punctuation or sentence construction if you are not confident in these areas. The point is not to compose beautiful prose, but to write down your flow of consciousness, your thoughts and emotions in the moment.

Do not self-censor. The minute you begin to think, ‘I can’t write that, it’s horrible’, or ‘These thoughts make me a bad person, so I can’t write them’, then what you write is not truly honest. However, noticing that you want to self-censor is interesting and important in itself, and worth writing about.

We all think, feel and act, so write about all three. Considering these three elements can be an important corrective, as we will see when we come to the right-hand page.

The right page: commenting on yourself

If we have a good day on a Monday then a bad day on Tuesday, it can be very difficult to imagine in the gloom of Tuesday how good we felt only the day before. Then, if we have a great day on Wednesday, it can be difficult to get in touch with how bad things felt only yesterday. This is because our emotional states tend to be discrete, self-contained, a world of experience in themselves, filtering in and heightening anything associated with that present-tense experience. For example, if we are delighted to be given the promotion we want at work then, in the bright light of that joy, ideas are more interesting, food tastes better, and jokes are funnier; or if we are crushed to be passed over for the promotion we thought was ours, in the dankness of that disappointment, ideas are uninteresting, food tastes drab, and jokes are pointless noise.

If we have a good day on a Monday then a bad day on Tuesday, it can be very difficult to imagine in the gloom of Tuesday how good we felt only the day before. Then, if we have a great day on Wednesday, it can be difficult to get in touch with how bad things felt only yesterday. This is because our emotional states tend to be discrete, self-contained, a world of experience in themselves, filtering in and heightening anything associated with that present-tense experience. For example, if we are delighted to be given the promotion we want at work then, in the bright light of that joy, ideas are more interesting, food tastes better, and jokes are funnier; or if we are crushed to be passed over for the promotion we thought was ours, in the dankness of that disappointment, ideas are uninteresting, food tastes drab, and jokes are pointless noise.

For these reasons, the mood captured on the left page on a Monday may be inaccessible by Tuesday. The right page is for meeting yourself on a different day, in a clearer and calmer state of mind, and adding commentary, perhaps a week, 2 weeks or a month later. You meet yourself as you were on the day you wrote, which may be quite different to the person you are in the moment you re-read your own words.

For some people, just the act of calmly reading your own words, which were written in heightened emotion, brings new insight into your own processes. To gain more from writing on the right page, it is helpful to consider 3 ego states and 3 modes of behaviour.

The right page: ego states

Reading your own words over time you may notice patterns, that when you are angry, sad, or fearful, you experience these moods or emotions in particular repeated ways. In Transactional Analysis (TA), a type of psychotherapy, there is a very helpful idea that can help us understand these patterns: that we have three discreet types of cognitive/emotional processes, named in TA the Child, the Parent, and the Adult ego states, capitalised to distinguish them from a physical person who is a child, a parent, or an adult. On the right page, it helps to distinguish whether the previously-written left page was written from the vantage point of the Child, the Parent or the Adult.

The Child is the state of mind – thinking, feeling and acting – we developed in childhood. Whenever we are under more pressure than we know how to manage, we return to the Child ego, the time when we were not in charge, were unable to make important decisions, and were subject to forces beyond our control. When reading and commenting on the journal that was written in high emotion, we would expect to recognise the Child.

A child does not have a clear sense of time, of past, present and future, and has emotions that are much stronger than intellectual capacity. For this reason, a child tends to think in universal terms, trapped in the eternal present tense. It is as if the child thinks ‘I am miserable now, so my life has always been miserable and always will be’, or ‘I am very happy now, so my life has always been wonderful and always will be’. With a child’s heightened emotions, s/he can go from the experience of universal misery because teddy is lost, to universal joy because teddy is found, within seconds and without any sense of contradiction. The physical adult, under overwhelming pressure and therefore in the Child ego, can therefore make universal and false generalisations that, in the moment, feel true, such as ‘you always criticise me’ or ‘you are never there when I need you’. When not over-generalising, a person under stress in the Child ego will think in dichotomies, in simple opposites, for example, ‘I am good and you are bad, therefore I must win and you must lose, I must be rewarded and you must be punished’, without any sense that reality is almost always more complicated than that.

In Transactional Analysis, the Child ego state is more than a general idea of how a child thinks, feels and behaves: it is particular to you, to your biography, to your experiences. So, for example, a child who adapted to a loving, supportive family will develop a quite different Child ego state to one who had to adapt to being neglected or abused. Under pressure and overwhelmed, the loved Child will be able to receive reassurance; whereas the neglected or abused Child will likely want to fight or will sink into isolation and despair.

The Parent ego state is the internalised carer and authority figure. We learn the Parent ego state by absorbing the influence of our own parents, how they set boundaries, how they loved and encouraged or chastised and belittled us. Like the Child ego state, the Parent is not just a general idea of a parent: it is particular to your own experience and becomes absorbed as an inner voice or commentary on yourself. The person whose parents were loving and reassuring will have a loving and reassuring Parent ego state that says, ‘You got this wrong, but that’s OK. What have we learned to help us have a second go?’ Without intervention, the person whose parents were punishing and undermining will have a punishing and undermining commentary that says, ‘You got this wrong, you idiot, and everyone can see it. You’ll never learn. Why do you even bother?’

The role of the Child and the Parent ego states is to recycle the developmental past, when the personality was moulded in our formative years. In its most negative form, the Child in us imagines we are doomed to repeat what has always been, because the voice of authority, the Parent, dictates it.

The third ego state, the Adult, is the part of us that lives in the present, the self-aware clear-eyed questioner who can stand back, analyse, and understand. When the left/right journal works at its best, we can see that under pressure the Child and/or the Parent wrote the left page, and the Adult adds comments of clarity on the right page, recognising the repeated and stuck patterns of the Child and the Parent.

The third ego state, the Adult, is the part of us that lives in the present, the self-aware clear-eyed questioner who can stand back, analyse, and understand. When the left/right journal works at its best, we can see that under pressure the Child and/or the Parent wrote the left page, and the Adult adds comments of clarity on the right page, recognising the repeated and stuck patterns of the Child and the Parent.

The right page: think, feel, act

When writing on the right page to comment on what was previous written on the left page, it can be helpful to remember that we have 3 modes of behaviour: we think, we feel and we act. Depending on our developmental experiences, our personality, our sense of ourself, we are likely to have a preference for thinking, feeling or acting. Considering all three when reading the left page can be a way to identify an imbalance, as follows.

An over-reliance on thinking, on cold analysis, on theorising, can be a sign that we are afraid of our emotions. This in turn raises the question, ‘How did I become afraid of my feelings?’, and shows the need to get in touch with emotions through work in therapy sessions.

A predominance of feeling, of huge emotions, jumping to conclusions about other people or oneself based only on how we feel, without the ability for cool analysis, raises the question, ‘What happened to me that I become so easily emotionally overwhelmed?’, and shows the need to develop analysis and action.

Writing that focuses largely or wholly on activity, without analysis or descriptions of feelings, will read like a list of events, as follows: ‘I went to the town centre with Sadie. I said the car needs looking at, she said it would be nice to watch a film or something, then I came home and checked the oil, the brakes and the carburettor. Sadie was annoyed with me. I don’t know why. I asked her what she wants me to do. She said that’s not the point. She’s crying. Now I’m in the dog house again. I don’t get it.’ Such a process raises the question, ‘What happened to me that I am out of touch with my own and others’ feelings, and find it hard to analyse personal interactions?’ The answers to such questions are always developmental, i.e. in childhood.

Mock example of the left/right journal

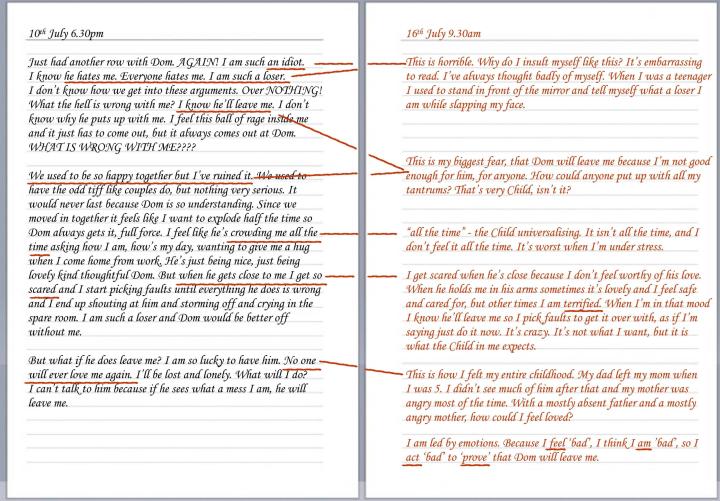

Below is a made-up example of what the left page may look like after a difficult encounter. This client, we’ll call her Christie, has come to psychotherapy because she fears that her repeated outbursts will finish her relationship with Dom. This is what she writes in her journal. (For each journal entry, click on the picture to open it larger in a new window, click in the new window if you wish to further enlarge it.)

Christie’s left page of the journal.

This is clearly a deeply unhappy woman who has suffered emotional trauma in childhood. By emotional trauma, we mean she has experienced a significant distressing event or events which she does not know how to process and move beyond. The stuck and unprocessed event therefore keeps resurfacing, unconsciously recreated in the present so that the trauma repeats in a continually unresolved cycle. The experience of trauma is therefore the exception to the ephemeral flow of emotions in the moment that are soon forgotten. Given something in the present that reminds us of the trauma, powerful unresolved emotions come flooding in. Sometimes the person is well aware of the traumatic event being replayed, but this is not always the case, so all the person knows is that they feel overwhelmed.

6 days later, at a time when she feels calm and composed, Christie writes her observations on the right page in red ink. Because she has had 10 psychotherapy sessions so far, she is able to: see the significance of her use of language; connect present events to her developmental past; identify the key reason for her outbursts; pick up the clues about her Child, Parent and Adult ego states, such as the universalising Child; and recognise that she is led by emotions, which means that at the heart of the emotional storm she jumps to conclusions about Dom based only on how she feels, without the ability for a more objective analysis.

Her right page notes are as follows.

Christie’s comments on the right page of the journal about the entry on the left page.

The left/right journal in a therapy session

Christie thinks there is more to learn from this entry and is desperate for the cycle of self-sabotage to stop, so she brings it to discuss in a session. I am able to see what Christie has understood from our sessions so far, and make further observations about the entry. During the session, she makes extra notes in blue pen, as we see below.

Christie’s journal with additional notes in blue made through discussion in a psychotherapy session.

As we see above, it is clear that Christie is in a cycle of self-blame and self-loathing – “Everyone hates me. I am such a loser … WHAT IS WRONG WITH ME????”, and fear of complete abandonment – “But what if he does leave me? … No one will ever love me again”, both in the universalising Child ego, i.e. this is based on her experience as a child, with an absent father and a mother who took her marital frustrations and anger out on her child.

When making notes on the right page, Christie missed her own phrase that she feels a “ball of rage” inside her “and it just has to come out … at Dom.” It becomes clear in discussing the journal entry in the session that Christie’s “ball of rage” is the anger she has carried all her life at her parents, which she has never expressed openly. We discuss in the session that it is likely not an accident that she missed this phrase when making notes, because she feels such shame at being so angry: shame because she feels anger is bad, having been on the receiving end of her mother’s anger; shame because she feels it is wrong to be angry at parents, as ‘who else was going to look after me?’; and shame because her anger carries the danger of losing Dom.

Dom, who has never deserved it, gets the anger that should have been directed by Christie at her parents. We discover there are two reasons for this. First, Christie’s shame at her suppressed anger towards her mother and father means that when it surfaces it is neither admitted nor understood, so it is directed elsewhere, at Dom. When Christie was a teenager, she used to direct this anger at herself, repeating her mother’s actions by slapping herself in the face and telling herself she’s a loser. Second, as a child, Christie’s mother used to follow her round the house to make jibes and snipes – ‘Look at the dog’s breakfast you’ve made of that! You will never amount to anything, just like your father’ – to the point that Christie would end up shouting back in hurt anger before running off to her bedroom to cry heartbroken tears. This has left her with a fear of proximity, of intimacy, of someone getting too close. So it is significant that Christie and Dom “used to be so happy together” when they lived in different places, and that since they “moved in together it feels like [Christie] want[s] to explode half the time”. For Christie, this new proximity feels dangerous. When Dom behaves in a caring way, walking round the house with her when she is home from work, asking how her day has been, it feels emotionally like a replay of her sniping mother on her tail. This phenonemon is called transference: Christie’s experience of her mother and feelings about her mother are transfered to Dom. Transference doesn’t happen at random, it needs a hook to connect the present and the past, which for Christie was being followed around the house. Because she hadn’t recognised this connection, she was bewildered that she was so furious at Dom, emotionally exploding then running away to cry in the spare room, re-enacting her childhood trauma of running away from her abusive mother. Thus she ‘proves’ to herself the message her parents gave her: that she cannot have a loving relationship because she is unlovable, that she therefore cannot be good enough for Dom, so he is bound to get fed up of her “tantrums” and abandon her, like her parents did.

The word Christie uses to describe her trauma process is “tantrums”. This is significant because it is a word a disapproving parent would use: this is Christie channelling her punishing mother in the Parent ego state. So in the session I ask her: what would someone who cares about you call your distress?

It also becomes clear in the session, from the clues in the journal entry, that Christie has somewhat idealised Dom: the Child inside her has made him the perfectly Good partner so that she can replay her opposite role as the Bad child, now the Bad girlfriend. I therefore ask Christie, with a smile, for a list of all Dom’s annoying habits, to bring him down from his pedestal, to start the process of thinking in terms of a more emotionally-balanced, realistic and accepting adult-to-adult relationship.

The benefits of the left/right journal

There are many benefits of keeping a left/right journal.

The left page captures a moment in time that would otherwise be largely or completely lost. At a later date, this enables greater insight, clarity and self-understanding when writing on the right page, particularly when the original entry was made by the Child recycling the difficult past and the commentary is added by the analytical present-tense Adult.

This means that, over time, when we are again in a mood like one we have makes notes on, we are more likely to be able to bring to bear the insight written on the right page. When this happens, we have new understanding in the moment of distress, so we have new choices, no longer tied to following the same circular pattern. The change is not usually immediate, of course: the old ways have been established for years, so the new insight will typically take time and practice to become more established than the old ways. In this way, the left/right journal acts as an ongoing record of all those accumulated insights and positive changes.

Entries over time can help us recognise an imbalance in the 3 modes of behaviour. Are we thinking at the expense of feeling and therefore at the expense of relational connection? Are we feeling so much that analytical thought and action becomes impossible? Are we focussed only on external practical actions, at the expense of considering the effect on relationships?

The journal can be of significant use in sessions, speeding up the rate of insight and therefore of desired change, and helping to set a clear agenda for sessions.

In the case of the imaginary client, Christie, her left/right journal entry and the session that followed established an agenda to work on:

• nurturing the child – still present in Christie’s Child ego state – who was crushed by her father’s absence, her mother’s anger, and by having no one on her side: how can this child, who blamed herself, accept that she deserves no blame and is allowed to be loved?;

• becoming more friendly with her own emotions, that she has a reason to feel angry at how she was treated by her parents, that it is her fear of getting in touch with her anger that gives it such dangerous potency so it bursts out;

• undoing the repeated pattern that reinforces trauma (called a game in Transactional Analysis) that leads her to re-enact the anger, isolation and abandonment she felt as a child;

• and, most basic and fundamental of all, giving the traumatised Child a space to breathe, to speak, to be listened to, so she has the visceral understanding that her presence, her experience and her honesty are valued.

About Ian Pittaway

Ian is a psychotherapist and writer with a private practice in Stourbridge, West Midlands. Ian’s therapy is integrative, chiefly comprising key elements of transactional analysis, object relations, attachment research and person centred therapy. Ian has a special interest in trauma recovery and bereavement.

Ian is a psychotherapist and writer with a private practice in Stourbridge, West Midlands. Ian’s therapy is integrative, chiefly comprising key elements of transactional analysis, object relations, attachment research and person centred therapy. Ian has a special interest in trauma recovery and bereavement.

To contact Ian, call 07504 269 855 or click here.

© Ian Pittaway Therapy. Not to be reproduced in any form without permission. All rights reserved.

You must be logged in to post a comment.